Reflections & Images - A Discovery Of Analog Film Photography

It all comes down to feeling. I simply enjoy the feeling of photographing with film the same way I enjoy playing an acoustic kit rather than a electronic one. It's my response to these tools that I cannot sacrifice for ease and convenience.

Decaf Journal is reader-supported. When you buy links through our site, we may earn an affiliate commission.

Disclaimer: My rambling below is not a contribution to the film versus digital dialogue, as I don't find the conversation constructive or worth engaging. The two are tools born of different times and necessities, tools with certain strengths and qualities of work flow which fit the creative process of some better than others, and it's the burden, privilege, and pleasure of each artist to discover and select which tools best fit their own process.

I stumbled into film photography by way of my mother.

Born in 1992, I was raised when celluloid still dominated the photo-capture landscape for professional and amateur photographers. As far as I can tell, even in the mid-90s the earliest digital cameras directed at consumers—the Casio QV-10 released in 1995 for around $700 USD, for instance—were priced just shy of $1,000 USD. Not necessarily economical for the everyday, family-event documentarian then.

My mother was this type of photographer, and while the act of photographing with film has an element of nostalgia for me due to my memories of her with a film camera, I'm not overly sentimental about the practice. I don't remember what camera she used in my early years, neither do I remember her taking photos even frequently. I do, however, remember other things.

I remember tagging along with her to drop off negatives for processing at our local CVS or Walgreens. I remember her passing the exposed rolls to the quiet technician standing behind the counter, which I could barely see over, ready to convert the little canisters into prints. And when we received those prints, I remember the developed negatives in their opaque plastic sleeves, unsure of their significance and the role they played in the whole exchange.

As fascinating as I found these trips to the lab, this is where my piqued interest with the whole ordeal ended as a child. I don't have the entry-into-photography story I so envy of others, and I never received a hand-me-down Super 8 or 35mm stills camera to run around with and document what I saw so near to the ground. It wasn't until much later, when I was taller—a teenager—that I very casually started taking photographs.

I believe I was eighteen or so when I stole my mother's Canon Rebel G2, which I still have in my possession, and I traveled with it on some of my early twenties' escapades. Most of the initial results were typical of beginning photographers, i.e., indistinguishable and unusable, the result of either over or underexposure, often combined with the wrong shutter speed. But those few frames I managed to expose properly, which I did so accidentally, evidenced a desire to capture the feeling of an environment or preserve a moment or memory.

In 2013, three years after graduating high school, I spent six months thru-hiking the Appalachian Trail, the footpath winding up the eastern coast of the United States from Georgia to Maine, and I brought my mother's camera with me the final 500 miles or so, from my birthplace in central Vermont on through New Hampshire and into Maine. Though the trail's total distance changes minorly each year due to trail maintenance detours, it typically sits around the 2,180 mile mark. Over a decade later, it's still hard to believe anyone can, or would deliberately choose to, make a journey that long on foot—I was twenty years old when I made that trek, and, regrettably, I have very few photographs of that time.

Months after completing our long-distance hike, my cousin (whom I hiked alongside) and I continued our vagabonding and headed for the American southwest, selecting to live out of a Toyota car truck—the Tacoma's predecessor—only slightly larger than our backpacks. Like modern Beatniks outfitted with ultra-lightweight backpacking gear, we took up residence on northern-Arizona, forest-service roads, camping most nights in the bed of our truck outside Sedona, then a sort of new age Mecca, sheltered by Juniper trees under the southwest's yawning and star-riddled skies.

We passed the winter and spring months of 2014 in that otherworldly, high desert region, and along the way we encountered hippies and self-named shamans, alien abductees and others who claimed to commune directly with inter-dimensional beings. Amid the serenity of the desert and the confusion of our peers, we considered our own place in the universe and what we were to do with our lives. We were both twenty-one, and our time spent there is one of the most memorable and most bizarre periods of my life; I look back on it and the photographs I took then fondly, in spite of—or perhaps because of—their flaws.

© Stephen Porter Whipple | Our backyard during our Arizona adventures, 35mm, 2014

At some point between my stretches of roaming and returning home, I found a Nikon FM2 in an antique shop in New England. I remember picking it up and feeling its weight in my hands. It felt good to me, the camera's bulk and density, and though I still knew nothing about manual exposure, I felt as though I could achieve something with that camera; my encounter with it felt consequential. The camera seemed to be in good shape and only $15 USD—it was in perfect condition, actually, and I had no idea of the bargain I'd found—so I bought it.

I believe there are pivotal moments that occur in our lives which largely go unnoticed. These moments aren't overtly life changing, nor are they seemingly momentous. They are quiet and stealthy, and I'm convinced that the series of these small occurrences and their accumulation, especially those that seem wholly insignificant, are what sets and changes the course of our lives. Though it may seem commonplace, as I look back on it now I can see that my purchase of that old mechanical camera was one of those moments in my life.

I continued to shoot photographs casually for a few years after I purchased my Nikon FM2, and I took the camera with me to Chicago for a brief bout of undergraduate studies, during which I took an Introduction to Photojournalism course. In that evening class, I was lucky enough to meet the work of photographers such as Jun Fujita and Vivian Maier, whose photographs I felt—and still feel—wordlessly but instantly compelled by. I also finally encountered the exposure triangle and, more importantly, comprehended it.

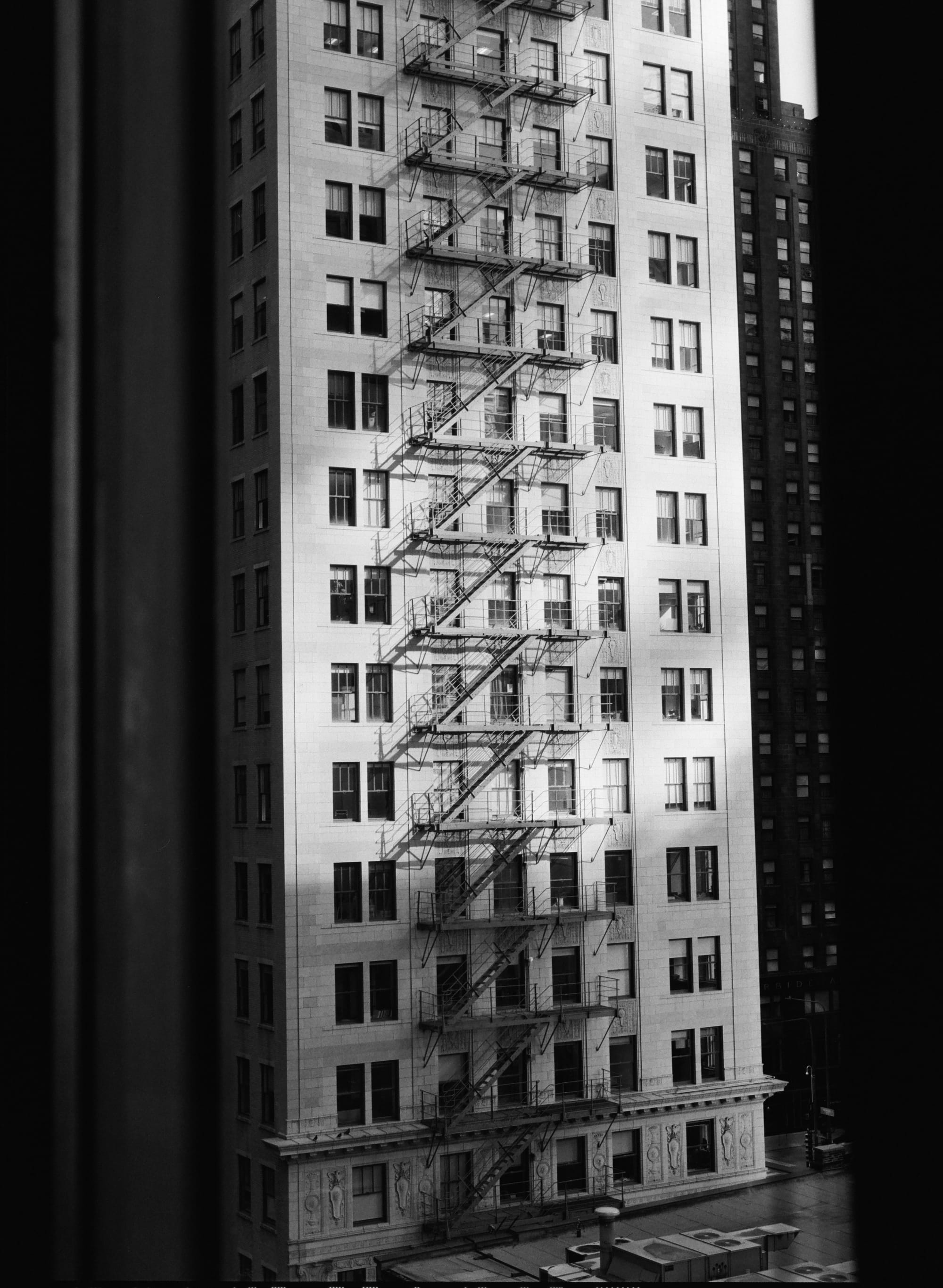

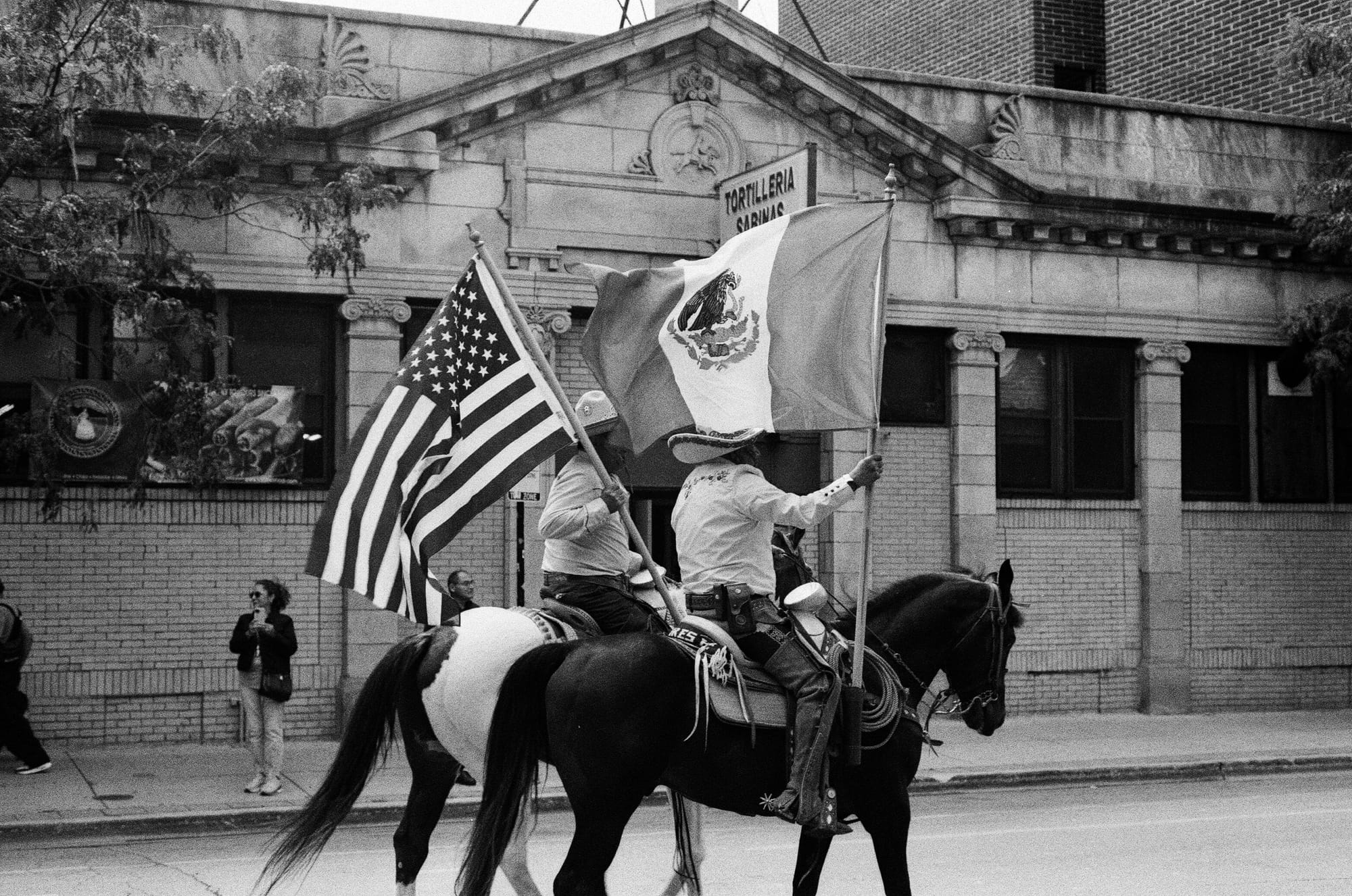

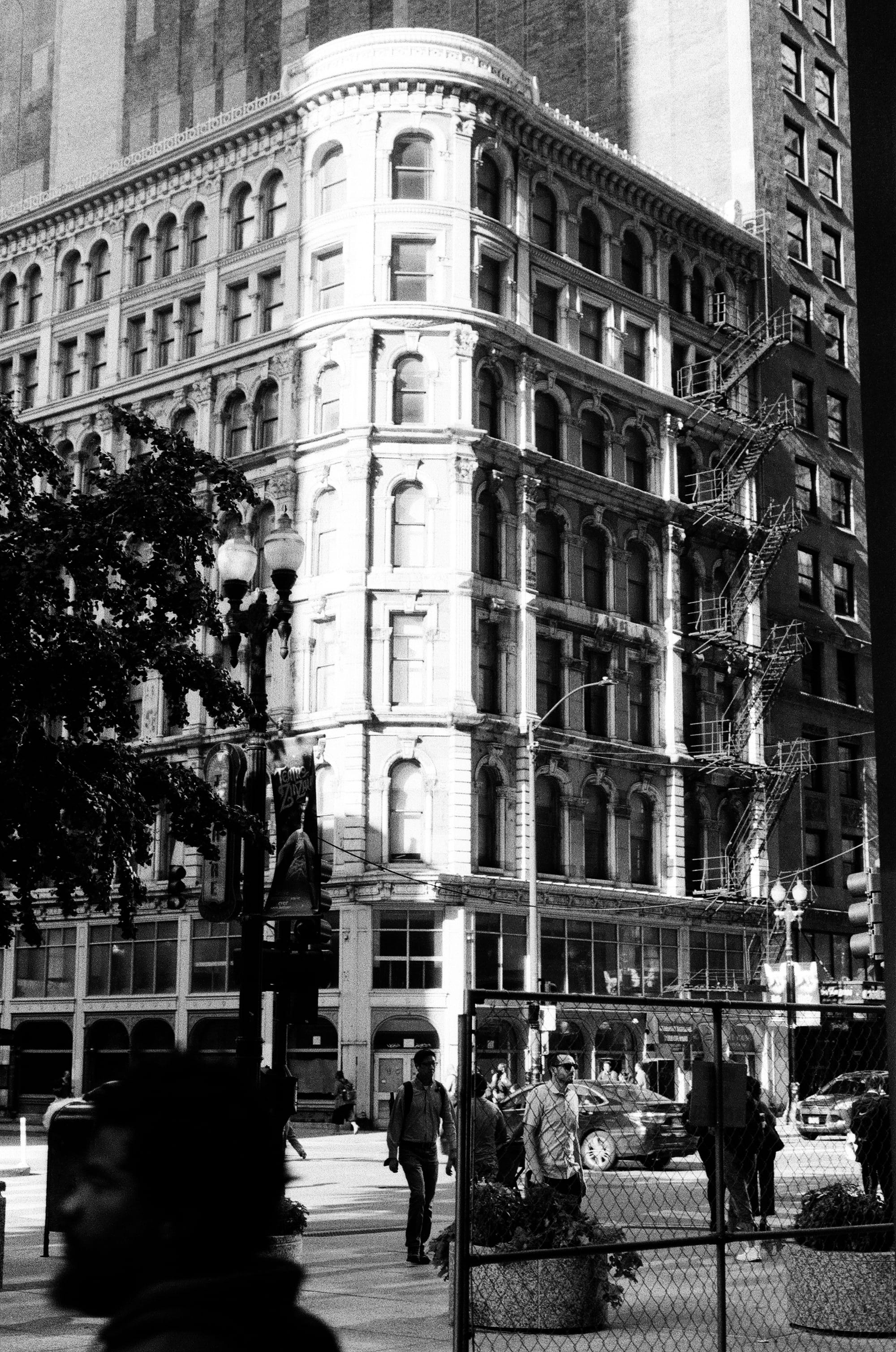

Chicago has been my home since 2018, and it's where I've developed most not just as a photographer, but as a person. Chicago is where I met my wife, and where our first child will soon be born. It's where I grew greatly in my understanding of and appreciation for film photography, and where I stumbled into filmmaking professionally. It's where I realized how mutually informing, regarding technique and storytelling, these two disciplines are, and Chicago is undoubtedly where I've taken the most photographs.

Last year, after four or five years shooting solely my Nikon FM2 and a 50mm lens, on both black-and-white and color stocks, I purchased a Nikon F3, a 28mm lens, a light meter, and shot predominantly black-and-white stocks—I also played with medium format for the first time as well and it was incredibly enjoyable. During those initial years, I was drawn by black-and-white greatly, and I toyed with but fought off the idea of avoiding color stocks altogether for a while. I finally gave in though, and I watched my photos improve exponentially as a result.

Prompted by writing this article, while sifting through the photographs I've taken over the years and recounting the travels and periods of my life they document, I wondered to myself why I was drawn to photography. Why is it image-making I gravitated to and not another craft, especially when my first love, in terms of the arts, was not photography, but music?

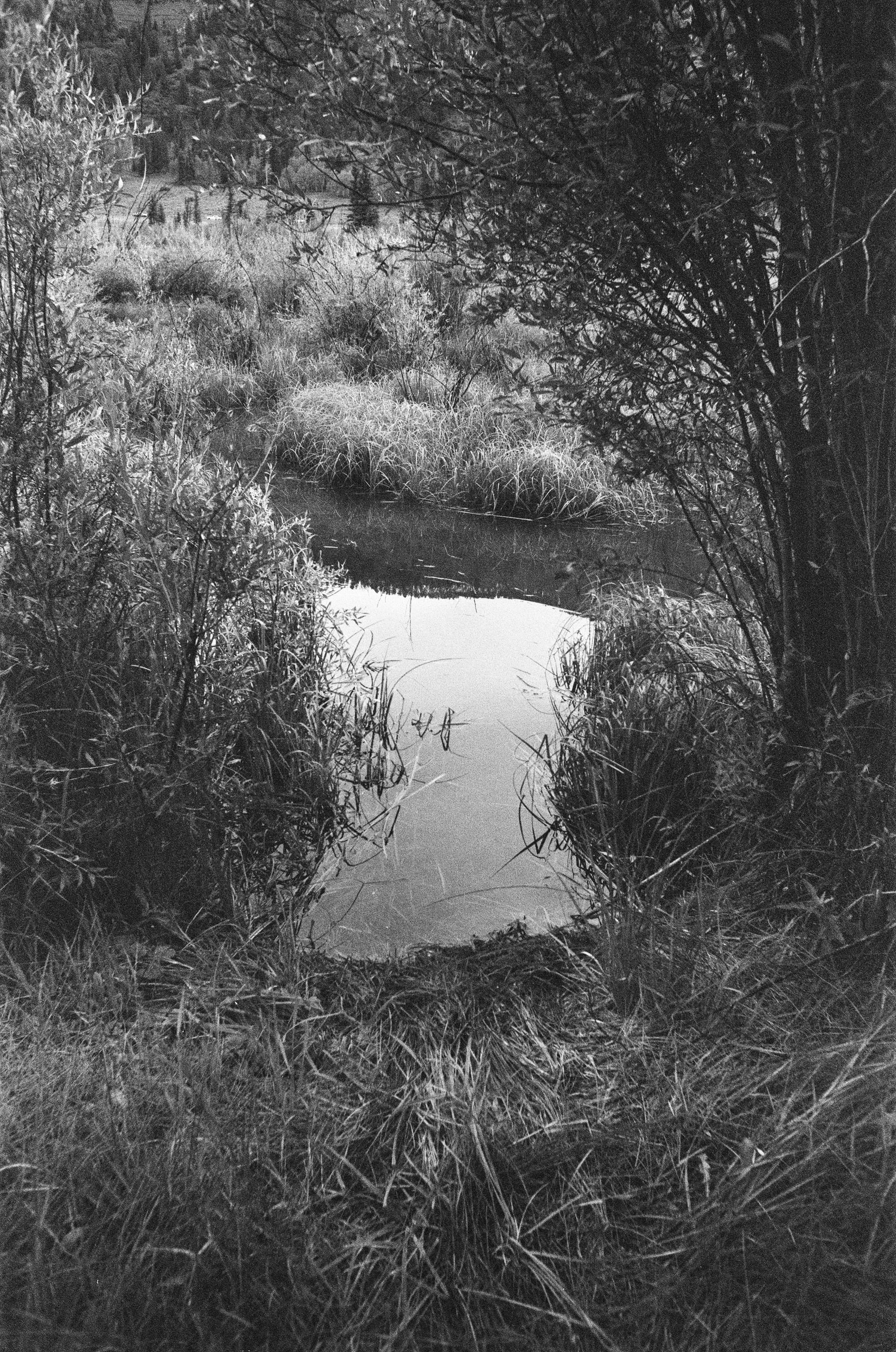

© Stephen Porter Whipple | Chicago, Wisconsin, and Iowa on 35mm and 120 b&w stocks, 2024

I grew up a drummer, the band's preserver of time. For some outrageous reason, my parents gave me a small drum kit for Christmas when I was two. How they put up with the racket I'm certain I made prior to the manufacturing of noise-cancelling headphones, I do not know, but I became extremely enthusiastic about drumming, I took to it naturally, and I spent my childhood and nearly two decades after pursuing the craft.

For a number of reasons, there came a point when I felt forced to give up the pursuit of drumming professionally, and it was then, while I was coming to terms with giving up that dream, when I found my Nikon FM2 in an antique shop. I had no idea then that simply looking through the viewfinder of that camera would direct my attention toward and eventually lead to storytelling through images professionally.

Being a drummer to me, though, was as much about interacting with and responding to the drum kit I was playing as it was about setting and maintaining time for the rest of the band, and whether I was simply stretching and tuning drum heads, improving form and endurance with rudiments, or playing a show with a band, I preferred and was always more satisfied when I played an acoustic kit.

I've found that my reason for this is tied to why I prefer, as do countless others, photographing with film. It all comes down to feeling. I simply enjoy the feeling of photographing with film the same way I enjoy playing an acoustic kit rather than a electronic one. It's my response to these tools that I cannot sacrifice for ease and convenience.

© Stephen Porter Whipple | Chicago, Vermont, and Colorado on various b&w 35mm stocks, 2024

Maybe most significant to me though is the sense of awe and inexhaustible, mysterious beauty I still feel when considering the act of trapping light from a specific moment in space and time on to a strip of celluloid. It conjures up simultaneous thoughts of temporality and eternity, and if I chase those thoughts long enough, they eventually prompt a sort of silent wonder and perplexity in me, a sense of overwhelmingness and wordlessness at the cosmic stage play our lives are both intertwined with and components of.

What any of it means—my fascination with preserving and tending to time in either sphere, music or photography—I do not know. The mechanics, tools, crafts are what I'm compelled by. I'm addicted to the sensations that result from my involvement in the disciplines, and I'm intoxicated even further by my contemplation of the processes altogether.

Do I need to answer what it all means? Can I answer what it all means or know where any of it will lead? I don't think so.

I am content with dedicating myself to a system I respond to, ritualistically setting out nearly everyday to perform a series of precise actions, and collecting images which recount a specific moment when light reflected off a person or object which I otherwise would not have seen had the light not revealed it by setting it apart from the darkness. There's something almost religious and reverent about it all.

© Stephen Porter Whipple | Chicago and Iowa on various b&w 120 stocks, 2024

Ultimately, had my mother not casually documented our family's gatherings, taken me along to drop off her negatives, and allowed me to steal her humble, everyday camera to experiment with, I may have never experienced or fallen into this world of pleasure and wonder—oftentimes frustration and confusion, too—that is film photography.

I'm so grateful she did, though.